Below are just a few general tips to consider when making scientific observations…

1) When it can be considered safe to do so, use all five of your senses: sight, hearing, touch, taste (aka. touching with your tongue!), and smell.

2) Use words to describe what is seen, felt, heard, smelled, and (if appropriate) tasted. When speaking English, most speakers use only a small fraction of the total number of words that are available to them. To help you increase the total number of descriptive words that you can summon to describe objects and events, consider using the two linguistic resources below:

– The Describing Words website, which provides a lengthy list of descriptive words after submitting a noun you wish to describe. (You might also find that the Related Words and Reverse Dictionary sites are both useful when creating descriptions.)

– Dr. Merritt’s Descriptive Word Bank – a Google Sheet with separate tabs for words related to sight, sound, touch, taste, smell, and time.

3) Notice details. In English, it’s sometimes said that the ‘devil’ is in the details, but for scientists, it’s often the teeny, tiny details that matter most. The fictional character Sherlock Holmes is perhaps the best embodiment of this simple mantra. In Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s original Sherlock Holmes novels and short stories, in the BBC’s Sherlock television series (2010-2017), and in the two most recent Hollywood films–Sherlock Holmes (2009) and Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (2011)–Sherlock Holmes is a larger-than-life private detective for whom no detail is too small to be overlooked. On the contrary, his uncanny ability to successfully outwit criminal masterminds and solve crimes is in large part due to his commitment to noticing objects and events that most other people either ignore, overlook, or dismiss.

– You, too, can develop Sherlock Holmes-type observational skills, but you should know that it takes lots of dedicated practice to develop such skills. You can start, however, by using Dr. Merritt’s Observations Assisters, a set of simple strategies (12 and counting!) to help you hone your powers of scientific observation.

– As for which details to take particular notice of, well that depends on what you are observing. The links below offer you some general advice regarding some of the details that scientists pay attention to when they make observations of organisms such as animals, bacteria, fungi, plants, as well as non-living objects such as rocks, streams, and the sky.

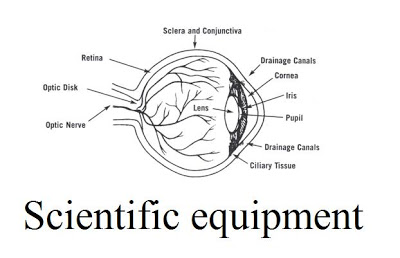

4) Break things into parts, then name and describe the parts. What we see, taste, touch, smell and/or hear, whether objects or events, can often be quite complex. A useful way of confronting this complexity is to break things into smaller or simpler parts and then observe each of the parts separate before once again considering the object or event as a whole. If you don’t know the name of something you see, consider making up your own descriptive name for it (at least until you find that others have agreed to name it differently).

5) Use analogies. If you’re not finding it easy to come up with the words you need to describe an object or event because it is entirely unfamiliar, consider trying to say what the object or event is like. Remember, someone once said the Earth’s moon looks like “green cheese,” and this particular analogical statement has managed to survive in popular culture for over 400 years.

6) Draw what you see and label parts of the drawing. You’ve probably heard the old adage, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Well, in scientific work, it’s often true. Drawings have always been an important aspect of science and you should consider using pictures even when you think words will do just fine. Plus, when you make a drawing of something, you’ve entered the second stage of a good description: creating a written record of it.

7) Be systematic. Consider approaching the object or event you wish to observe with a specific plan. For example, you might start at the top of an object and work your way down to the bottom. Or, you might start with the outside of an object and work your way towards the inside.

8) Use tools. You will rarely find a scientist working without a set of tools. Whether a microscope, a magnifying lens, a dissection kit, a ruler, a mass balance, a camera, a rock hammer, etc., scientists are some of the world’s most frequent tool users. Many new observations are made possible by the use of tools. Don’t be afraid to use them in your observations, and don’t be afraid to invent one if you don’t have or can’t find the right one…for example, a toothbrush can be an excellent tool for cleaning the dirt or dust off of a rock.

Last updated: April 2017